by Efrat Yerday

Abstract: This article reviews works of contemporary female artists of Ethiopian origin active in the Israeli art field. I analyse the subjects in their work and argue these artists are presenting their attitudes towards the ‘white gaze’. Though constantly subjected to it by the Israeli hegemony and the Western masculine discourse, they are notably decreasing their consideration of it. They broaden the restricted field of action that seems designated for them and alter its boundaries. Drawing on theorists of gender, postcolonial theory and theory of art, I demonstrate how these artists are promoting an agenda that reflects their lives as black women in Israel. Influenced by recent socio-political changes and a decline in representations of black women on TV and in visual arts, these artworks were increasingly exhibited in solo and group exhibitions.

Keywords: Ethiopian Jews, ethnicity and race, identity, political art, visible minority, women and gender

In my teenage years in the 1990s, everyone in my surroundings straightened her hair. The hair salons I entered refused to touch my hair because I wanted to keep it in its natural form and not straighten it. That is why I often took care of my hair at home. In the DIY method, we straightened our hair with an iron. The ironing might have slightly burned the scalp, but the result was impressive – the unruly hair was straight, disciplined and manageable. Over the years, I realised this experience is not unique to my friends and me and that in different places in Israel and around the world, girls with coily, kinky or crisp hair like mine found different ways to restrain their hair.

In the context of gender analysis of the feminine beauty ideal, ethnicity/race and hair are inseparable. Like skin colour hierarchies, the perception of hair is bound to the Eurocentric beauty model and is culturally organised according to it (Moore-Robinson 2008). The public discourse in Israel does not discuss head hair as a cultural identity component. The research of art history also To Be Black and Beautiful in Israel → 71

does not consider this issue as gender or ethnic matter, echoing the absence of representations of black women. This absence is rarely regarded, and only since the late 2010s has this trend started to shift. Ethiopian artists – both graduates of the best art academies and artists with no formal higher education – introduce new representations into the field of local visual culture and demand the public and the hegemonic cultural institutions consider these representations. Alongside this trend, new critical forces demand to discuss these representations (or their absence).

This article argues contemporary artists are broadening the restricted field of action that seems to be designated for them by Israeli hegemony and the Western masculine discourse in general, alter its boundaries, and consequently change the discourse and its content. This article will demonstrate how contemporary artists of Ethiopian origin are promoting an agenda that reflects their lives as black women in Israel.

White Gaze – Black Lives

The ‘white gaze’ is a critical tool for examining racial and gender visibility, and it concerns the white beauty ideal that shapes the experiences of women and men of all ethnicities. But the distance between the different identities to this ideal affects each life experience differently. Being a black woman in a white, patriarchal society forces black women to subordinate themselves to the white eye watching from the outside, ‘as though our lives have no meaning and no depth without the white gaze. I’ve spent my entire writing life trying to make sure that the white gaze was not the dominant one in any of my books’, said the novelist Toni Morrison (Rose 1993). In her novel The Bluest Eye, Morrison presents the ideology behind the beauty myth and wipes out the white gaze (Burcar 2017). The increasing presence of African American women in the media in recent years is still narrow and limited. They are mostly featured in minor and secondary roles in Americans films and TV shows (Schooler et al. 2004). Moreover, most of the representations are of biracial or light-skinned women. That is one reason scholars are calling for the rejection of the black-white dichotomy (Butler 2013; Deliovsky 2008).

According to Naomi Wolf, ‘beauty is a currency system like the gold standard [. . .] in assigning value to women in a vertical hierarchy according to a culturally imposed physical standard, it is an expression of power relations in which women must unnaturally compete for resources that men have appropriated for themselves’ (2002: 12). Normative beauty is Eurocentric and is targeting all non-white people (Munafo 1995). The discussion of black identity and blackness has developed extensively in the United States. Intellectuals worldwide, especially from Third World countries, were influenced by this discussion. Many of them even acquired their higher education in American metropolises (Ahmad 1992). Globalisation, being overall characterised 72 ← Efrat Yerday

by American values and interests (Chomsky 2012), has also contributed in various ways to the immediate link between the American context and other contexts (Ram 2003). In Israel, critical researchers who dealt with the Mizrahi identity – Jews of colour from Middle Eastern and North African origin – began to write about this identity in postcolonial terms, claiming Israel constitutes internal colonialism. Those researchers brought forth the idea that the situation of Mizrahi Jews is related not to their traditional and not modern culture but to the dependent relations that were born in the gathering of exiles of Ashkenazi and Mizrahi Jews in the land of Israel. According to this theoretical framework, Jewish ethnos does not exclude only Palestinians but also (Arab) Jews (Shenhav 2005; Shohat 2001).

Some sociologists compared the Mizrahi situation to the American model of racism against black people (Shitrit 2004), while other approaches stemmed from orientalism in Europe and the genealogy of oriental perception in time and space (Kazum 1999; Shohat 1988); some have integrated the postcolonial school with orientalism and the concepts of recognition and multiculturalism (Shenhav and Yona 2008). Newly proposed models trace the idea of white trash and non-American models (Hashash 2017; Lamont et al. 2016). In what follows, I would like to expand this body of knowledge by referring to a black, non-Mizrahi presence within the Israeli sphere.

Visual Representations: Race and Gender

The perception of race and ethnicity is valid and relevant concerning hair (and not only skin colour). ‘Whitening’ black hair in white culture is reinforced by the feminist perspective – extending to the fields of visual culture and plastic art. One should note the idea of ‘hair whitening’ refers to transforming black, tightly curled hair to an uncoiled, straight one. Such actions, however, are applied not only on the hair but also on the actual skin: black women around the world lighten their skin by various means, from make-up to chemical bleaching and laser surgery. Some chemicals reduce the amount of melanin pigment, while others affect the skin in other ways such as peeling. These bleaching materials were initially designated for medical use to aid with skin diseases such as facial skin spots, which impairs the uniformity of the skin tone, but over time became lightening or bleaching products for the whole face. According to an assessment published by the World Health Organization (WHO 2011) on skin bleaching, 77 per cent of Nigerian women said they regularly use skin-lightening products, as well as 61 per cent of women in India and 40 per cent of women in China. These products, popular among women of colour, were classified by WHO as hazardous to health and were therefore banned in several European countries where the dark-skinned population uses them. These extreme phenomena of skin whitening have not been noticed in Israel so far, but this does not indicate the extent or existence of it, because To Be Black and Beautiful in Israel → 73

the subject has not been studied and therefore is not present in the public or academic discussion.

In the Israeli critical academic discussion, ‘blackness’ is mostly discussed concerning the Mizrahi Jews. The issue of blackness in Israel has many important aspects, but one of the most prominent of them is tied to gender. The beauty standard in Israel is a white woman with straight, blonde hair, ultimately embodied in the model Bar Refaeli, whose image is displayed wherever we look. While most women – of all ethnicities – struggle to meet this beauty standard, black women cannot even strive for it, because it requires them to be born again in a different colour. Black women follow a beauty regime that deviates from the ‘normal’. The Israeli discussion of blackness forces Ethiopian women to put more effort into their appearance than others. While trying to hurdle the Israeli beauty standard, black women often try to tone down or downsize their black appearance in different forms and levels of ‘whitening’ to avoid drawing unnecessary attention to their colour abnormality. In her dissertation, researching how Ethiopian students deal with racist phenomena, Shula Mola (2018) names a significant part of their conflict as ‘the struggle for being ordinary’. It is a daily struggle, trying to be ‘normal’ or ‘ordinary’ in a society that sees you as the ultimate ‘other’. Mola argues this strategy is doomed to fail, since it does not allow a full experience of self.

In an article in the Ma’ariv newspaper on 19 August 2016, Miss Israel 2013, Titi Ayanaw, of Ethiopian origin, speaks about this subject and explains why she decided to move to New York and try her luck modelling there:

I feel that fashion companies in Israel, when launching campaigns and choosing spokesmodels are afraid to put dark-skinned women in the front [. . .]. They don’t give opportunities here for the different, the other. There are a lot of dark-skinned models who are amazing, but they are employed as side-kicks or as boosters [. . .]. My potential can be realized more over there. That’s my feeling. The international industry is indeed much bigger and more competitive, there are millions like me, but at least I am legitimate, not different and unique because I am black. (Levin 2016)

Coily, kinky or crisp hair, especially in an Afro, attracts a lot of attention. This is probably one of the reasons women of Ethiopian origin ‘whiten’ their hair or restrain it in different ways. Skin colour and hair type carry many social and historical meanings. The whiter you are, the more socially and morally ‘correct’ you are, and, respectively, the straighter your hair is, the better and more beautiful you are. Like in Israel, the beauty standard in Ethiopia is influenced by the Western model of beauty, so beauty is defined by fair skin and non-African features. It should be noted the Ethiopian national narrative differs from the general ‘African’ postcolonial one. Ethiopia considers itself superior to other peoples in Africa, and overall. Over the years, Ethiopia has separated itself historically, religiously and nationally from the rest of Africa. This distinction – internationally accepted by both Western and African countries – has developed in Ethiopia for several reasons. The main ones are the commercial 74 ← Efrat Yerday

relations with the East; the absence of European colonialism as opposed to widespread colonialism in other African countries; and, most importantly, the development of Ethiopian civilisation, including the development of an independent Ethiopian script and of Christianity as a state religion. The latter two reasons serve the national narrative of Ethiopia as a justification for the Ethiopian people’s cultural superiority over other African peoples and even European peoples.

The first signs of a cultural discourse on the subject of the hair of black women in Israel are expressed in the docuseries Afro, created by Einalem Mengesto (2017), in which she tracks several women of Ethiopian origin and documents them as they talk about their ‘hair complex’. One of the interviewees, Tikva Yissachar, the writer of the blog Ma’ase Bemekuzelet (The tale of the curled one), speaks of her dreams of straight hair: ‘My wild fantasy when I was little was to have straight hair [. . .] I always took a towel after the shower and wrapped it on my head. And I would put it [. . .] so it will be long, and I imagined it was my hair, that I have straight hair.’ The activist Kasa Getu recalls her mother’s responses to her Afro: ‘I was coming home, or my sister was coming back home, and we have Afro hair, so she always tells us – do something with the hair . . . When my mom tells me “do something with your hair” – that’s how white people perceive you, and it sure ain’t pretty.’ Getu further describes her bitter experiences with attempts to straighten her hair:

When I was in the eighth grade, I went to get my hair straightened; everyone straightened their hair. We went to the central bus station and had the straightening done. But when I got back home, my whole scalp peeled off. For almost a year, my mom had to sleep right next to me and cut the pillow off my hair. This entire year we were sure my hair would never grow back, I had bald spots everywhere, and it was one of the scariest things.

The public discussion about discrimination and racism against black people in Israel precedes the academic one, yet even the public discourse takes place within narrow and strict borders. Black women, usually curly headed, are extensively busy with whitening it or trying to release it from the white gaze. Whereas the white gaze is unavoidable, black women often wish to be absorbed in the whiteness without receiving any special attention – or, in the words of Mola, the desire to be ‘ordinary’. Straightening the hair or bleaching the facial skin is a practice of assimilation. Israeli women wishing to integrate into the main discourse and become an integral and normal part of it must first go through a certain degree of normalisation, and hair straightening is one mean to this end. Shlomit Aylin Goren, interviewed in Afro, also describes the process she went through from her years in high school to the employment world: ‘I don’t go to job interviews like that [. . .]. I pick it up; I arrive more presentable. And then when I’m in, they soon realise the hair comes with me [. . .] When I was young, when I was in high school, I used to pick it up, up, up, up. Tightened it and put pins, and pins and pins so it wouldn’t go wild; I’m over it.’To Be Black and Beautiful in Israel → 75

A quick and preliminary examination of the black figures of Ethiopian origin seen on TV in Israel shows that most of them are straightening their hair – from Titi Aynaw; to Tahonia Rubel, winner of season 5 of Big Brother; Hagit Yaso, winner of season 9 of the reality singing competition A Star Is Born; and PM Pnina Tamano-Shata. It is interesting to note that black figures who are not of Ethiopian origin, mostly American, have mildly straightened or even natural unhandled hair. Unlike the Ethiopian Jewish women, black women from other communities sometimes wear their natural hair. Atalia Pierce, from the Hebrew community of Dimona, for example, who competed in the reality show The Voice in 2012, came to the first audition with natural, loosely picked up hair (though she straightened it as she got ahead in the competition). The model Yushivia Jones, also a member of the Hebrew community, is modelling with short, coily hair. Nickia Brown, an American citizen who competed in A Star is Born in 2010, came to audition wearing dreadlocks. Comparing the different groups living in Israel can reveal different strategies, as well as unfamiliar values and motivations. These examples are a glimpse of the change in public discourse in the last decade.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the renowned Nigerian American author, claimed Barack Obama would have not been elected president if his wife, Michelle Obama, had remained in a natural Afro hairdo (Rifbjerg 2014). The portrait of Miss Israel 2013, Titi Aynaw (see Figure 1), taken after her

Figure 1: Portrait of Titi Aynaw (© Daniel Kaminsky, Ma’ariv, 2016).76 ← Efrat Yerday

hair was transformed to soft-looking waves, embodies this principle of social demand for changing and whitening black hair. The struggle of Ethiopian women to be Israeli in every sense and aspect of life includes a daily battle with hair. It seems all women have hair issues, but for black women, this is a daily struggle with unique meanings for a group with a negatively stigmatised phenotype – being ‘black’.

Sexuality and Racism

For black women, the definition of beauty is highly limited: a black woman must be thin and tall with voluptuous breasts and, the recently added member to this list, bountiful buttocks. Celebrities like Jennifer Lopez and Beyoncé have made the big buttocks a part of the black female beauty standard. While the world’s most popular singers are Rihanna and Beyoncé, the beauty model for black women seems to have expanded, but in fact, it has re-shrunk, with identifiable restrictions. Black women, strong as they may be, are still kept under the thumb of the white gaze, and the attempt to adopt Beyoncé or Rihanna as a model of beauty is as doomed to failure. No women are allowed to be themselves, let alone black women. Also, the racist experiences black women report are often immanently sexual. Unlike men, who report of more violence related stereotypes, stereotypes on black women are related to their sexuality (Lamont et al. 2016: 12). Any deviation from these models of beauty may mark an unusual and strange woman, especially when a black woman is at hand. Black women are therefore subjected to double oppression: sexist and racist. They should regiment both their female sexual bodies and the colour of their dark skin, as well as everything it is identified with.

While issues of black hair are publicly spoken about in the United States, and most black women still make tremendous efforts to deny the social order of straightening their hair, only a few have found the strength and awareness to establish a community to support natural hair. In Israel, there is no framework for this discussion, and such a debate has not yet begun. A black woman in Israel cannot walk around with a natural Afro hairdo and feel ‘not unusual’, and she will certainly not do so freely outside the borders of Tel Aviv. A black woman wearing dreadlocks or an Afro is stared at much like a woman’s hairy – that should have been shaved – armpit. Most black women who try to walk around with natural hair in the public sphere are hackled and stared at; many of them will submit to the accepted norm and will not talk back or raise an opposing voice. Those who nevertheless choose to ignore the judicial white gaze are inevitably ones who have gone through a personal process of self-acceptance or grew in an exceptionally supportive environment.

It is important to remember the black communities in Israel are a numerically negligible minority, constituting less than 2 per cent of the population. The black groups in Israel conduct themselves as separate communities – Ethiopian To Be Black and Beautiful in Israel → 77

immigrants, African refugees, Hebrews, black Bedouins and black Palestinians – nullifying the chance of consolidating the different groups by common African origin. The separation of these small groups makes it difficult to evoke a significant change, contrary to what can be seen in the support groups in the United States, as their size might constitute a significant market share, and therefore cause a considerable change in their visibility in the public sphere.

However, several black female figures with a different appearance have emerged on the television screen, deviating from the preset mainstream routes. For example, we note Inbar Bogale, who led the protest against police brutality in May 2015 while carrying her blonde dreadlocks as a political statement. Cabra Casay’s name was associated with ‘authentic’ music, and in this context, her natural hair could be accepted. Singer Esther Rada paved her way out of the Israeli mainstream when she targeted the international crowd from the beginning of her career. What distinguishes Rada from other black performers in Israel is her choice to sing mainly in English and to brand herself as something else. Under these circumstances, Rada’s decision to release a cover album of the songs of Nina Simone, an African American singer, identified with the struggle for equal rights in the United States, both in her lyrics and in her activism, is not perceived negatively as ‘otherness’. These black women deviated from the mainstream highroads and appeared on TV with un-‘whitened’ hair. Each of them paved a unique path for herself, but together they open the road for others and change the power relations in the field of visibility and visual culture in Israel.

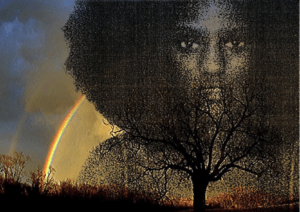

In 2007, the artist Smadar Elias painted a self-portrait with loose hair and planted it in an open landscape (see Figure 2). This piece is full of sarcastic irony, when the artist chooses to pose for her portrait as if she is emerging from a tree planted in an uninhabited surrounding, a kind of African savannah, with a shining rainbow on its side. The photograph reconstructs the stereotypical representations of blackness: primal, primitive, generic – representations that are perceived by the white gaze as equivalent to nature itself. Elias turns her gaze to Africa, the original habitat of black people, but the contents the artwork embodies are not nostalgic or romantic, but political (Dekel 2013: 122). Elias presents herself and her round Afro as magnificent and beautiful. The connection to Africa resonates with a contemporary critical discourse, the postcolonial discourse, and it establishes a culture that exists independently and not relatively.

The issue of removing the white gaze from the figures of black women in Israel, as can be seen in Elias’s piece, is more easily identified in the United States, with the recent generation of a broad movement of women implementing ‘black is beautiful’. For them, black hair is something worth leaving as it is to adorn their heads. Moreover, some do so out of a perception of one’s colour and hair as what makes her unique, and as such, they are beautiful. The roots of this movement can be found in the 1960s and 1970s, when Afro hairdos adorned the heads of many black women, from Angela Davis to Diana Ross. 78 ← Efrat Yerday

Angela Davis calls the revolutionary fashion style of the 1970s ‘Revolutionary Glamor’, and in this cultural, political and aesthetic sense, the Afro expressed racial pride. This connection between fashion and political statement also offered a vital gender aspect of autonomy for black femininity opposing the accepted, Eurocentric one (1998: 24). In this context, one can recall Noliwe Rooks’s famous remark that although we do not know precisely what Davis was accused of and even imprisoned for at the time, we all remember her Afro (1996: 6). Similarly, artists such as Hirut Yosef and Nirit Takele put forth other representations and colours in their artworks.

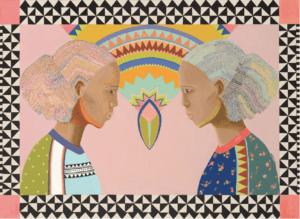

Hirut Yosef creates pieces that incorporate international and local languages and reflect her sense of pride in her origin’s culture and the women in her life, especially her mother and grandmother. The piece ‘Elelta’ shows two women in profile; their African hair is done in a typical Ethiopian hairdo of tight braids that end with loose, un-straightened Afro hair (see Figure 3). Among the artistic influences absorbed by Yosef, one can see the impact of street culture and graffiti, futurism, feminist art, black art and motifs from the world of computer graphics. Yosef writes a blog titled in English ‘Color is my Native Tongue’, metaphorically challenging the hegemonic demand to Hebrew language and Israeli culture (Ratner 2018). This sentence captures the spirit behind Yosef ’s artistic work, combining bright colours and binding them to her heritage: from her birth in colourful Ethiopia to her arrival to Israel at

Figure 2: Untitled, by Smadar Elias, 2007.To Be Black and Beautiful in Israel → 79

the age of five. Colours are a central part of her work, and they symbolise the various colours in Ethiopia: the clothes, the food and the flourishing green landscape. Some of the figures in her works are adorned by somewhat of an aura to symbolise their power and uniqueness – marked by a round frame or by a crown. She names the characters Mulu and the Beta Clan. Another interesting motif in her work is 1984; although related in Western culture to the dystopian book by George Orwell, for Yosef 1984 represents something else – the year of her arrival to the state of Israel.

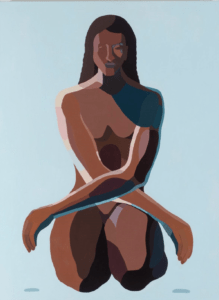

The artist Nirit Takele paints in acrylic in a unique style. She often depicts Ethiopian women in Israel in the context of the struggle for social justice and visibility. This painting from the 2017 series Justice to Yossef Salamsa shows the special attention the artist puts on gender and ethnicity, as she focuses on the intersecting dimensions of oppression subjected on black women in Israel (see Figure 4). This is rooted in the awareness of the ability to resist, and the power women have to operate with personal agency. The painting shows a black woman; her hair is long and loose, and she stands against a blue background that does not reveal any precise location in space. The woman kneels with her hands crossed over each other. The crossing of the woman’s hands is reminiscent of the gesture that became the hallmark of the Ethiopian summer protest of 2015. Protestors went out on the streets and demonstrated, raising their crossed hands to symbolise the community’s oppression. In this context, it may

Figure 3: ‘Elelta’, by Hirut Yosef, 2014, acrylic on wood, 101.6 × 139.7 cm.80 ← Efrat Yerday

be suggested that Takele intertwines the oppressive experience of a member of the community, Yossef Salamsa, who was arrested on false pretences by the Israeli police, and the intersectional oppression of black women in Israel – being both women and black.

The artwork of Zaudito Yosef Seri revolves around coal, which she minces and grinds as a spice and later consolidates the crumbs into perforated surfaces that look like black lace. Coal holds two conflicting qualities: primitively roughness on the one hand, and fragility on the other. For Yosef Seri, the coal represents her attempts to trace her childhood home and memories. She

Figure 4: Untitled (woman), by Nirit Takele, from the series Justice to Yossef Salamsa, 2017, acrylic on canvas, 90 × 120 cm.To Be Black and Beautiful in Israel → 81

immigrated to Israel from Ethiopia in 1991 and has no memories of her birth country. In the Israeli neighbourhood she grew up in, the smells evoked sparks of distant memories: coal in the bonfire, roasted coffee, Ethiopian bread and dishes. Identifying scent as an anchor to any lost roots accompanies her artworks. While the roughness of coal classifies it as inferior, Yosef Seri charges it with delicate and noble qualities as she moulds it to elegant lace. This practice echoes the experience of constant visibility through the white Israeli gaze and resists its negative connotations by creating different ones such as elegance, nobility and delicacy.

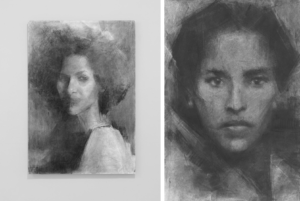

Tigist Yoseph Ron’s charcoal drawings also challenge the conventional images and connotations of Ethiopian women. In the transition between Ethiopia and Israel, women played a key role. The women in Yoseph Ron’s life – her mother, in particular – were a source of creative inspiration and are embodied in her works. The women in her images are her keens: mother, sister, grandmother and aunt who become universal women. In the mixture of negative images attributed to these women, Yoseph Ron uses the gentle, soft and sensitive qualities of drawing in charcoal (see Figures 5 and 6). The artist is deeply moved by the mental and physical strength of women who grew up in the non-Western world. The powers of these women stem not from higher education but from dealing with the everyday challenges before and after the immigration to Israel. Arising from a certain blurring, the facial expressions of the characters evoke awe and admiration. Directing the gaze

Figure 5: Hirut, by Tigist Yoseph-Ron, 2018. | Figure 6: Yalemwork, by Tigist Yoseph-Ron, 2018.82 ← Efrat Yerday

towards them make the viewer want to be with these women and learn from them. These women from her personal life are becoming part of the history of inspiring women.

The animated video series Go Back to Where You Came From by Esther Wanda, a graduate of the visual communications department in Holon Institute of Technology, features four videos: ‘Go Back to Where You Came From’, ‘A Real-Life Queen of Sheba’, ‘Bambo Niger’ and ‘You Don’t Sound Ethiopian at All’. These titles are quotations of sentences shouted at Wanda in the public sphere. In this artwork, she combines narration of everyday statements regarding her ethnicity with an Ethiopian style melody, played on krar (Ethiopian string instruments). The narrator’s hair appears in Afro in the first video and braided in the other clips. In ‘A Real-Life Queen of Sheba’, the audio says, ‘You are very beautiful, I swear, real-life Queen of Sheba, like the Ethiopian who won, maybe Titi or Tahonia’. This statement emphasises the flattening experienced by black women in Israel; they are perceived as a unified group, indistinguishable from each other as individuals. When a programme featuring a prominent Ethiopian figure is broadcasted, women of Ethiopian origin who live in Israel report they are called on the street by the name of the TV persona: Titi, Tahonia, Hagit Yaso and so on. In Figure 8, the artist emphasises her neatly non-Western braided hair by posing the woman with her back to the audience. In Figure 9, the feminine figure’s hair is braided. This time, she is facing the viewer, with monkeys in a zoo cage hanging on ropes that resemble her black braids. This artistic positioning seeks to foreground

Figure 7: Declaration Of Independence, by Zaudito Yosef Seri, 2017, coal, glue, epoxy and water, 2 × 0.70 m.To Be Black and Beautiful in Israel → 83

the diminishing stereotyping of black women in Israel who choose to walk around in the public sphere with their natural hair and the insults they receive on this performance.

On 14 March 2019, the exhibition The Color Line opened. Curated by Zaudito Yossef, it was the first exhibition that gathered six women artists of Ethiopian origin. The main purpose of the exhibition was to have an independent voice that critically deals with the white gaze. I was invited to write the

Figure 8: Detail from ‘Go Back to Where You Came From’ by Esther Wanda, 2017, animation.

Figure 8: Detail from ‘Go Back to Where You Came From’ by Esther Wanda, 2017, animation.

Figure 9: Detail from ‘Go Back to Where You Came From’ by Esther Wanda, 2017, animation.84 ← Efrat Yerday

text for the exhibition, which included one of its goals: ‘An attempt to ‘blacken’ the field of art in Israel in contrast to ‘whitening’ efforts’ (Yerday 2019).

The artworks reviewed in this article, influenced both by changes in the social and political field in Israel and by the infiltration of black women’s representations into the television and various visual spheres, have been exhibited in group and solo art exhibitions throughout the country at an increasing rate in recent years. It is worth noting that some of the contemporary works stem from direct opposition to the framework of art studies and the contents taught in art academies. The lack of representation of black figures in the curriculum and the default selection of content from and about Western culture during these studies have often led Ethiopian artists to take a stand of resistance and create ‘colourful’ works. In one of my conversations with Nirit Takele, she said that when she started Shenkar College, she painted in bold colours, but she soon noticed she did not see her colour anywhere around. They were all white people painting in white, and the brown figures and colours in their works were always service providers or part of the background. Following this, she decided to enlarge the territory of the brown body in her artworks.

Another artist, whose name will remain unmentioned, shared with me one of the racist statements made by one of her esteemed teachers, who spoke about many Africans in southern Tel Aviv. The teacher used negative, humiliating and racist terms to describe this area. At first, this led the artist to shut down, but later it motivated her to open up to another aspect that drives her even today – to paint more and more dark-skinned figures. Adding to this experience some of the social-economic obstacles that most artists of Ethiopian origin must overcome, the path is challenging. As bell hooks (1996) phrased it: ‘I longed to be an artist, but whenever I hinted that I might be an artist, grown folks looked at me with contempt. They told me I had to be out of my mind thinking that black folks could be artists – why, you could not eat art’. Academic frameworks can be regarded as a miniature scaled representation of the elite of society, and the exclusion of black women’s representation in this framework, in fact, reflects the biased reality in the outside world. ‘Colourful’ works created by artists of Ethiopian origin allow them to maintain their unique voice and not to be swallowed up in the ‘universal’ mood, thus marking their uniqueness – in terms of culture, ethnicity and gender, and in most cases in class. This presence, the result of daring and persistence, to bring forth visual representations of black femininity in art and television, offers a variety of options to choose to be both black and beautiful in Israel.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this article was published in Hebrew in Migdar: Journal of Gender and Feminism 5 (2018).To Be Black and Beautiful in Israel → 85

Efrat Yerday is a PhD candidate in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Tel Aviv University. She is a teacher, activist and board member of Association for Ethiopian Jews. She has a master’s degree in Politics and Government from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev and is researching the fluidity of citizenship in Israel. She established the Ra’av (Hunger) publishing house in Beersheba and edited its first book of translated poetry, Kushila’imashelahem (A temporary anthology of black poetry). In 2010, she established the Young Ethiopian Students blog, challenging the establishment and academic narrative of the absorption of Ethiopian Jews. From 2015 to 2018, she headed the research group ‘Ethiopians Jews Rewriting Their Story’ at Van-Leer Jerusalem Institute. Email: efratayerday@gmail.com

Anthropology of the Middle East, Vol. 14, No. 1, Summer 2019: 70–86 © Berghahn Books doi:10.3167/ame.2019.140105 • ISSN 1746-0719 (Print) • ISSN 1746-0727 (Online)

References

Ahmad, A. (1992), ‘Orientalism and After: Ambivalence and Cosmopolitan Location in the Work of Edward Said’, Economic and Political Weekly 27, no. 30: 98–116.

Burcar, L. (2017). Imploding the Racialized and Patriarchal Beauty Myth through the Critical Lens of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. Journal for Foreign Languages, 9 (1), 139–158.

Butler, J. (2013), ‘For White Girls Only? Postfeminism and the Politics of Inclusion’, Feminist Formations 25, no. 1: 35–58.

Chomsky, N. (2010), Hopes and Prospects (Chicago: Haymarket Books).

Davis, A. Y. (1998), ‘Afro Images: Politics, Fashion, and Nostalgia’, in Soul: Black Power, Politics, and Pleasure, (eds) M. Guillory and R. Green (New York: New York University Press), 23–31.

Dekel, T. (2013), Transnational Identities: Women, Art and Migration in Contemporary Israel [in Hebrew] (Tel Aviv: Resling).

Deliovsky, K. (2008), ‘Normative White Femininity: Race, Gender and the Politics of Beauty’, Atlantis 33, no. 1: 49–59.

Hashash, Y. (2017), ‘“We Are All Jews”: White Trash, Mizrahi Jews and Intersectional Marginality in Israel’ [in Hebrew], Teoria Ve-Bikoret 48: 249–264.

Hooks, B. (1996). Art on my mind: Visual politics.

Kazum, A. (1999), ‘Western Culture, Ethnic and Social Closure: The Background of Ethnic Inequality in Israel’ [in Hebrew], Sociologia Israelit 1, no. 2: 385–428.

Lamont, M., Silva, G. M., Welburn, J., Guetzkow, J., Mizrachi, N., Herzog, H. and Reis, E. (2016), Getting Respect: Responding to Stigma and Discrimination in the United States, Brazil, and Israel (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

Levin, M. (2016), ‘Titi Aynaw: Model Don’t Get Opportunities Here Because of their Skin Color’ [in Hebrew], Maariv, 19 August, http://tmi.maariv.co.il/celebs-news/ Article-553943.

Mengesto, E. (2017) Afro, Israeli Public Broadcasting Corporation, https://www.kan. org.il/program/?catid=1113.86 ← Efrat Yerday

Mola, S. (2018), ‘“I Am Completely Ordinary”: Jewishness, Israeliness, and Whiteness as Identity Anchors in Ethiopian-Israeli Students’ Techniques for Coping with Racism’ [in Hebrew], Gilui Daat 14: 13–42.

Munafo, G. (1995), ‘“No Sign of Life”: Marble-Blue Eyes and Lakefront Houses in the Bluest Eye’, Lit: Literature Interpretation Theory 6, nos 1–2: 1–19.

Ratner, D. (2019), ‘Rap, Racism, and Visibility: Black Music as a Mediator of Young Israeli-Ethiopians’ Experience of Being “Black” in a “White” Society’, African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal 12, no. 1: 94–108.

Ram, U. (2003), ‘The Big M: McDonald’s and the Americanization of the Motherland’ [in Hebrew], Teoria Ve-Bikoret 23: 179–212 .

Rifbjerg, S. (2014), ‘Interview with Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie at the International Authors Stage, Copenhagen’, The Royal Library of Denmark, May 2014.

Robinson-Moore, C. L. (2008), ‘Beauty Standards Reflect Eurocentric Paradigms – So What? Skin Color, Identity and Black Female Beauty’, Journal of Race and Policy 4, no. 1: 66–85.

Rooks, N. M. (1996), Hair Raising: Beauty, Culture, and African American Women (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press).

Rose, C. (1993), ‘Interview with Toni Morrison’, 7 May, https://charlierose.com/ videos/18778.

Schooler, D., Ward, L. M., Merriwether, A. and Caruthers, A. (2004), ‘Who’s That Girl: Television’s Role in the Body Image Development of Young White and Black Women’, Psychology of Women Quarterly 28, no. 1: 38–47.

Shenhav, Y. and Yona, Y. (ed.) (2008), Racism in Israel [in Hebrew] (Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad).

Shitrit, S. S. (2004), The Mizrahi Struggle in Israel: Between Oppression and Liberation, Between Identification and Alternative 1948–2003 [in Hebrew] (Tel Aviv: Am Oved).

Shohat, E. (1988), ‘Sephardim in Israel: Zionism from the Standpoint of Its Jewish Victims’, Social Texts 19/20: 1–36.

Shohat, E. (2001), Talking Visions: Multicultural Feminism in a Transnational Age, vol. 5 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

Wolf, N. (2002), The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used against Women (New York: Harper Perennial).

WHO (World Health Organization) (2011), ‘Mercury in Skin Lightening Products’, http://www.who.int/ipcs/assessment/public_health/mercury_flyer.pdf.

Yerday, E. (2019), The Color Line (catalogue), exhibition curated by Z. Yosef at Sapir College, Sderot.